Denver’s lakes may freeze over this winter, but underneath, there’s something lurking — waiting for the warm weather to return to strike.

It’s not anything as big as the Loch Ness Monster — in fact, the threat here is microscopic.

It’s toxic algae.

The green, slimy organism may seem relatively harmless — after all, it’s not like it has legs or fins to chase you down. But to Alan Polonsky, it’s a major part of his world.

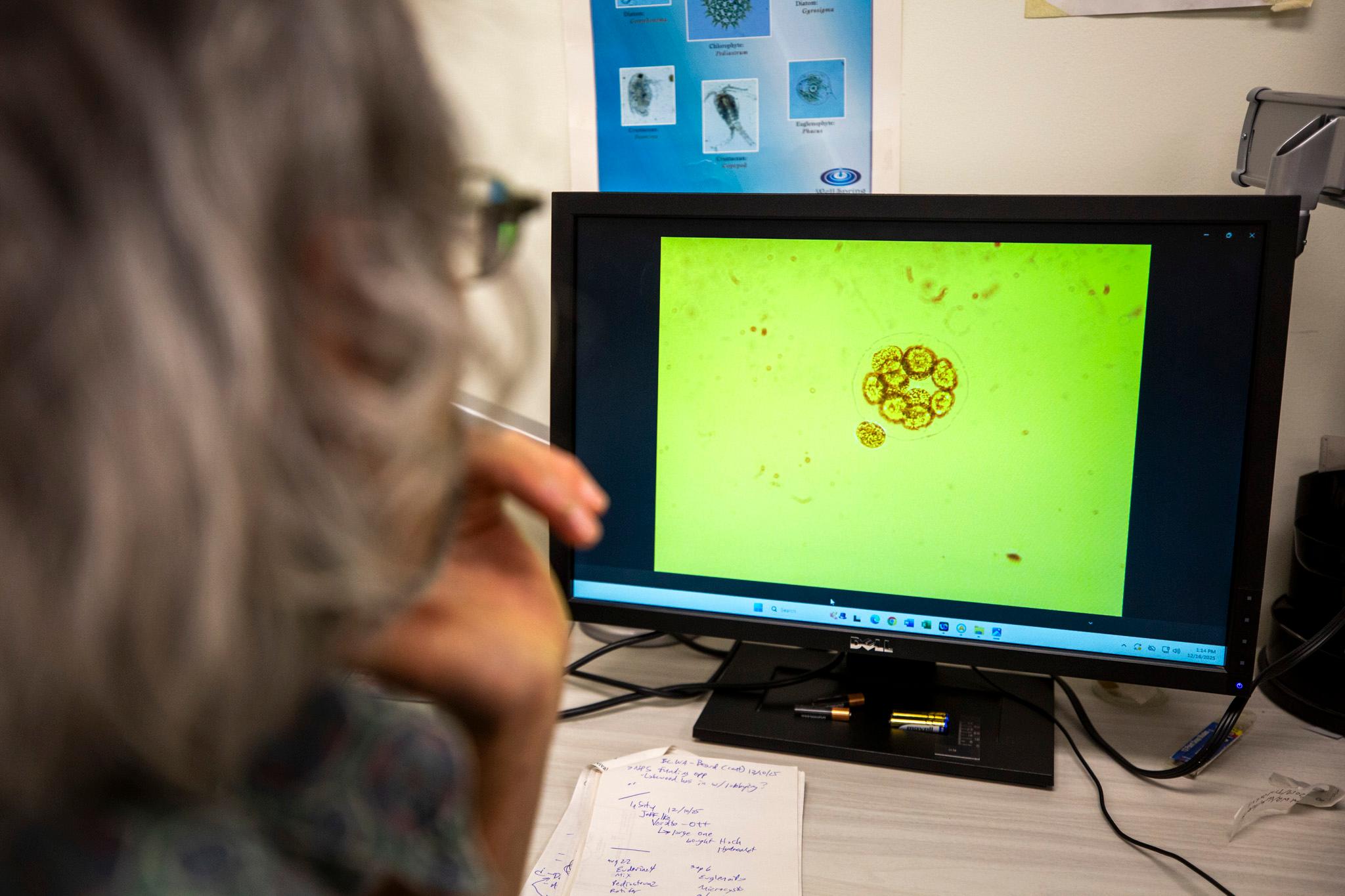

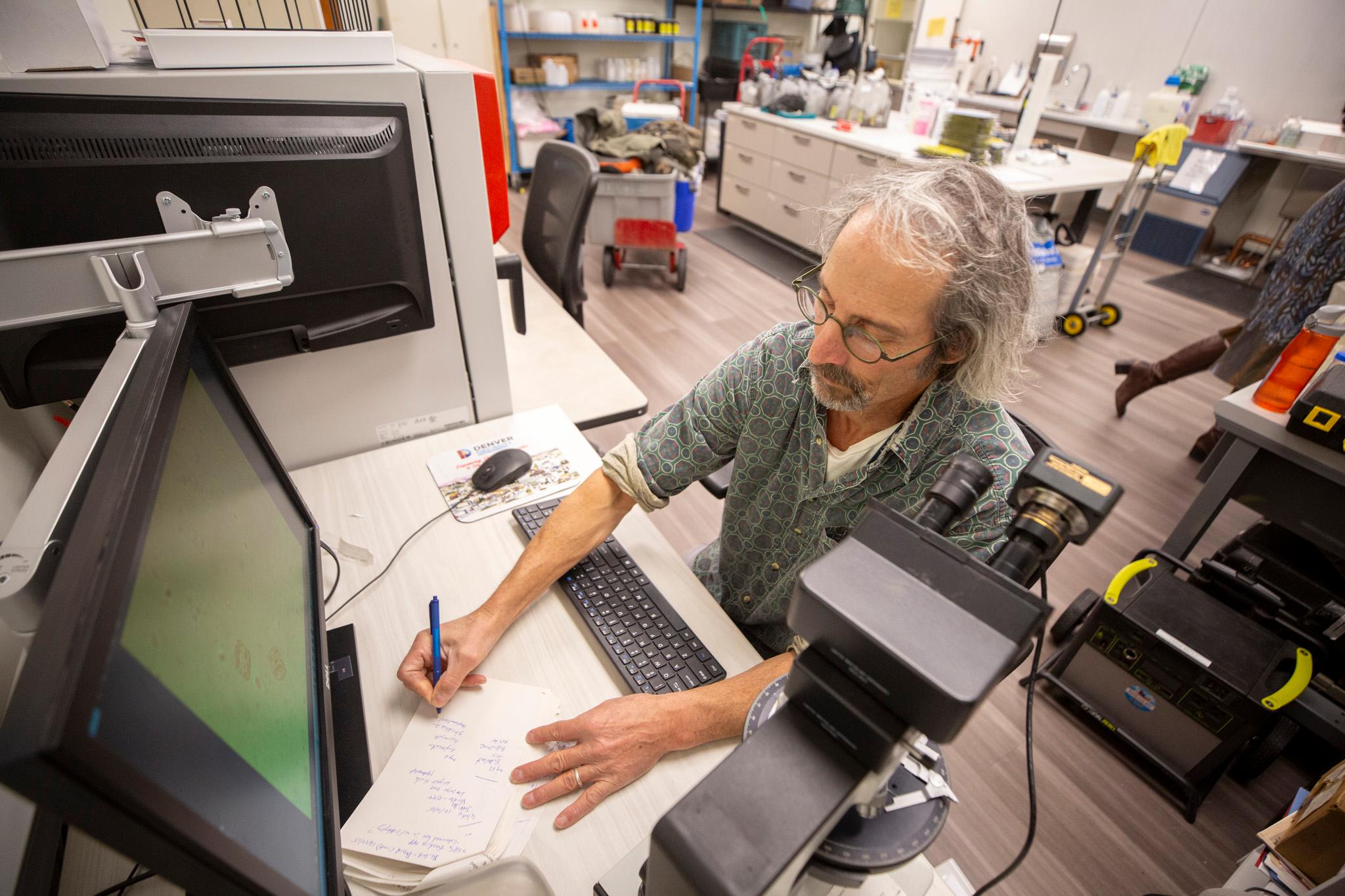

Tucked away in the city offices of the Wellington E. Webb Municipal Office Building, Polonsky often sits in a windowless lab hunched over a microscope. Here, he analyzes samples of water he’s taken from lakes across Denver.

In particular, Polonsky, an environmental analyst who has worked with the Denver Department of Health and Environment for over a quarter-century, is concerned with blue-green algae, the kindthat is most dangerous to humans, animals and the general health of a lake.

“It is a public and environmental health issue, and we want to manage the lakes in a way that minimizes this,” he said.

What is blue-green algae?

There are nearly 200,000 recorded species of algae, and likely as many more unrecorded species, according to online database AlgaeBase.

Not all are harmful, Polonsky notes.

“This guy right here, that's a green algae, and so that's like good fish food, good aquatic life food, and it's not a harmful algae,” Polonsky said while showing Denverite a water sample taken from Sloan’s Lake in September.

On the flip side, blue-green algae is toxic. Swimming or drinking in it could result in skin irritation, gastrointestinal symptoms, fevers and even liver damage.

Blue-green algae is so prevalent because it has a distinct advantage over its non-toxic brethren: It’s great at finding nitrogen, which algae needs to survive.

“If a lake has limited nitrogen in the water, blue-green algae doesn't necessarily care,” Polonsky said. “They'll just go to the surface and they'll suck it out of the air.”

That leads to major blooms that you might see on the surface of some Denver lakes during the summer. If blue-green algae is blooming, the surface might look like thick pea soup or spilled paint.

Even though blue-green algae is toxic to humans and animals, Polonsky said it’s important to achieve a balance between safety and letting nature run its course.

“It's believed that [blue-green algae is] what created [the Earth’s] oxygen-heavy atmosphere,” he said. “You don't want to kill all the algae, but you don't want too much of it. So you try and strike that balance. That's the challenge for parks is to strike that balance.”

How does the city test for toxic algae?

In September, Polonsky took Denverite to Sloan’s Lake to collect samples for algae testing.

Sloan’s Lake was the perfect place to do it — the lake has been home to the city’s most intense concentration of toxic algae blooms, due in part to the lake’s extreme shallowness, which has led to yearly mass deaths among its fish population.

The process took no more than 10 minutes. He took two plastic containers, dipped them into the water, and that was it.

“Sometimes we're looking for trends over time, and so we'll try and replicate the same place and the time of year and all that stuff,” he said. “Sometimes we're responding to a call from parks, a concern about algae, so we will sample from multiple places there. That might be for places that are representative of where people would be exposed to the algae, so maybe a shoreline or where people would be hanging out.”

From there, Polonsky takes the samples back to his lab, where he puts a drop or two into a microscope slide.

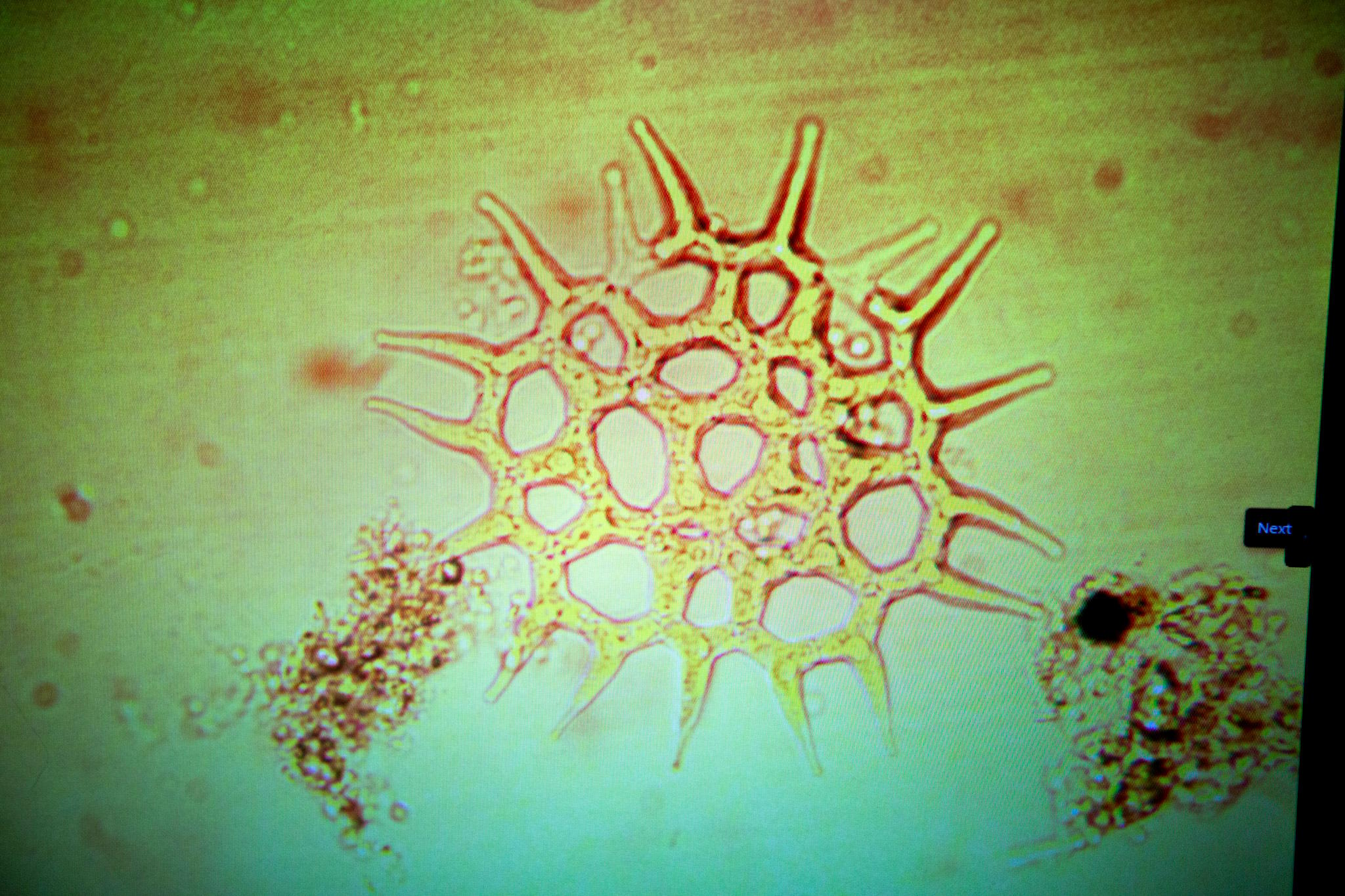

Underneath a microscope, Polonsky will see different bacteria, some of which signal a prevalence of blue-green algae. There’s microcystis, which looks like a cluster of peas, or chroococcus, which resembles a CT scan of a brain. It’s not an exact science — after all, there are countless types of blue-green algae and bacteria — but Polonsky’s eyes are trained to see the signs.

If he sees signs of blue-green algae, he’ll perform a formal cyanotoxin test to gauge the level of toxins in the water. And, if the toxins are high enough, Denver’s government will post notices at lakes warning visitors not to drink or recreate in the water.

Should I be afraid of the water?

Sure, not many reasonable people are choosing to take a dip in or eat fish caught from Denver’s lakes. But blue-green algae blooms are prevalent across the state.

Polonsky said once you’re aware of the issue, you won’t be able to stop seeing it.

“If you know where to look, probably all of us have black widows at our house,” he said. “You just need to know where to find them. It's the same thing with algae.”

But Polonsky says that’s not a reason to be afraid of what lurks below. To him, awareness is freeing.

“Knowledge is a good thing,” he said.